How To Tell If Someone Is A Jew

Religion is not central to the lives of well-nigh U.S. Jews. Even Jews by religion are much less likely than Christian adults to consider faith to be very important in their lives (28% vs. 57%). And among Jews as a whole, far more study that they discover meaning in spending time with their families or friends, engaging with arts and literature, being outdoors, and pursuing their education or careers than find meaning in their religious faith. Twice as many Jewish Americans say they derive a corking bargain of meaning and fulfillment from spending time with pets as say the same almost their organized religion.

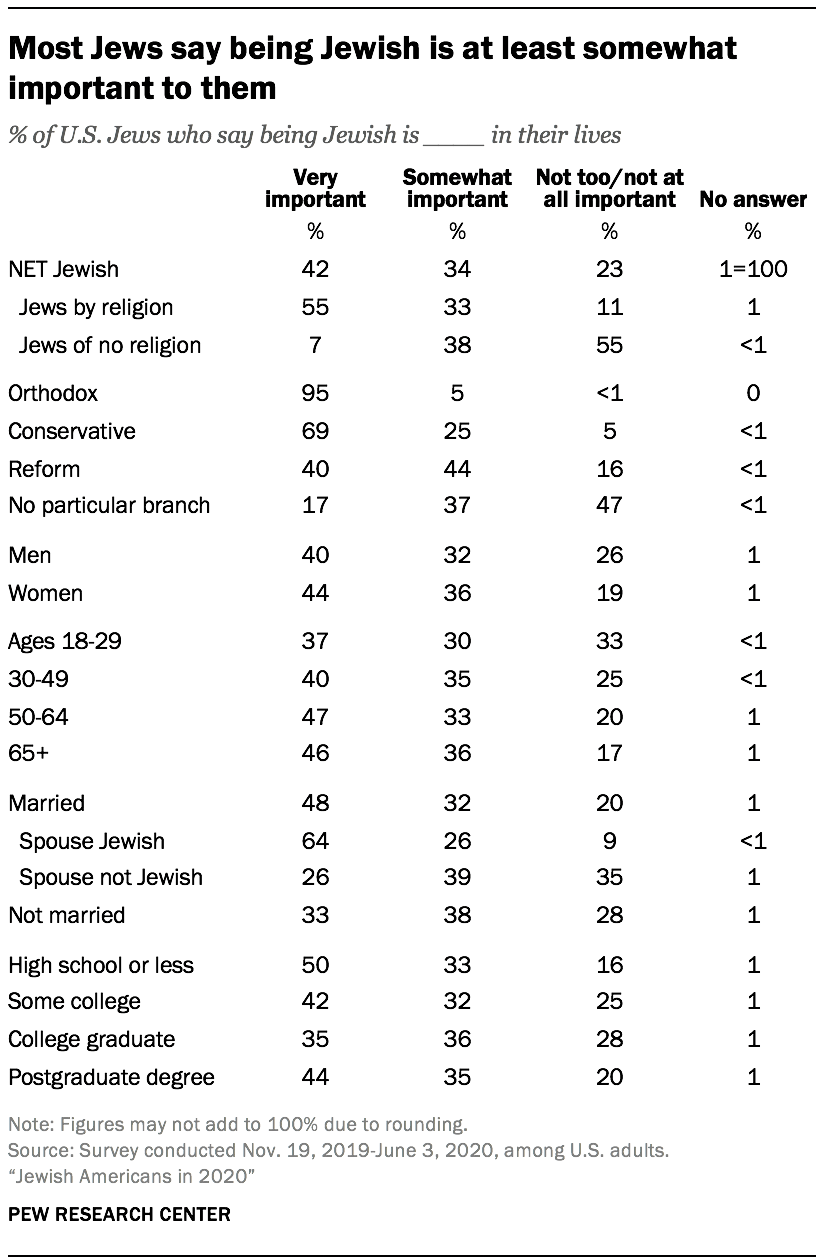

And nevertheless, fifty-fifty for many Jews who are non particularly religious, Jewish identity matters: Fully three-quarters of Jewish Americans say that "beingness Jewish" is either very important (42%) or somewhat of import (34%) to them.

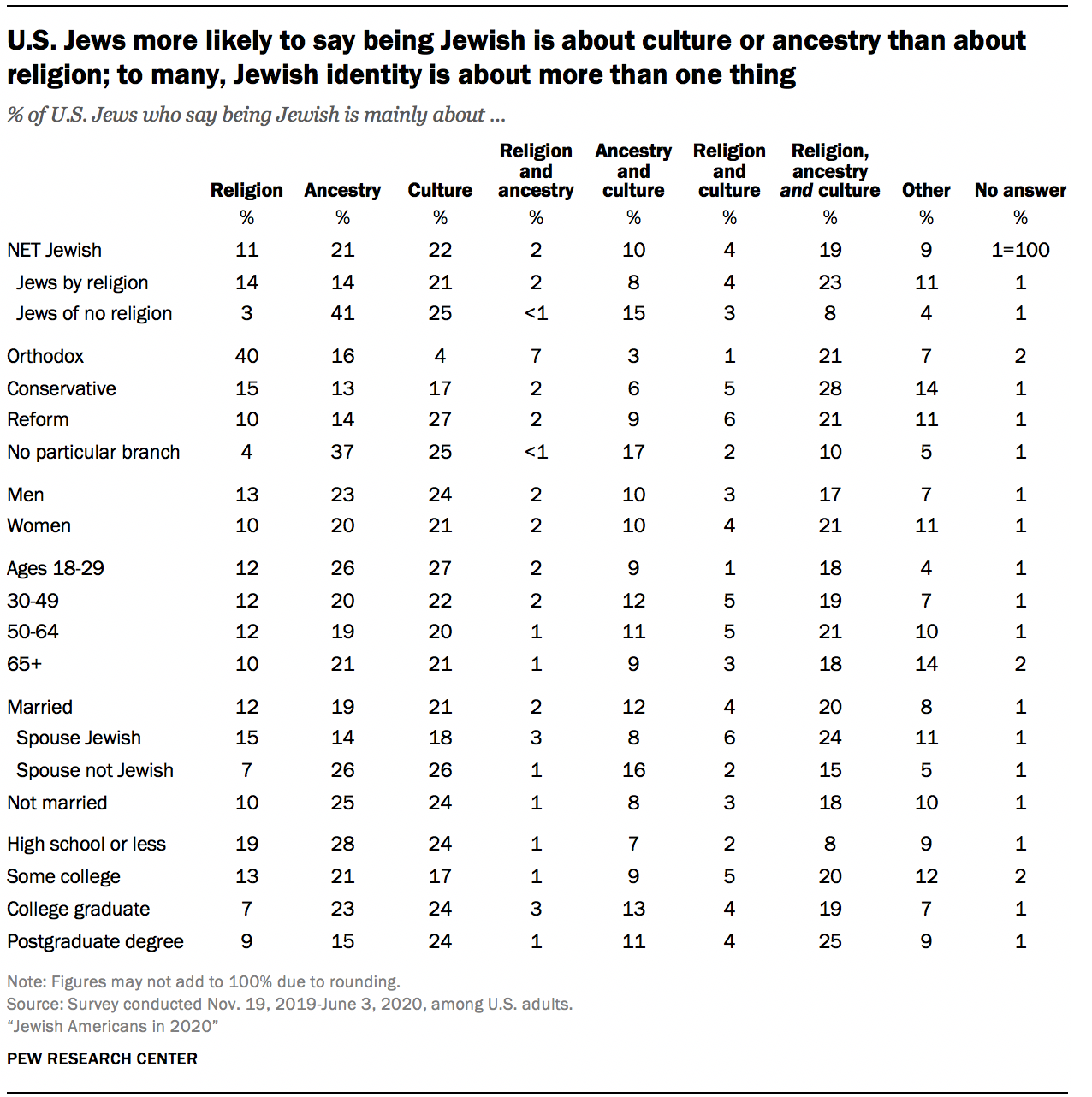

U.Southward. Jews do not have a single, compatible answer to what existence Jewish means. When asked whether existence Jewish is mainly a matter of religion, ancestry, civilisation or some combination of those things, Jews reply in a wide multifariousness of means, with just one-in-ten saying it is only a matter of organized religion.

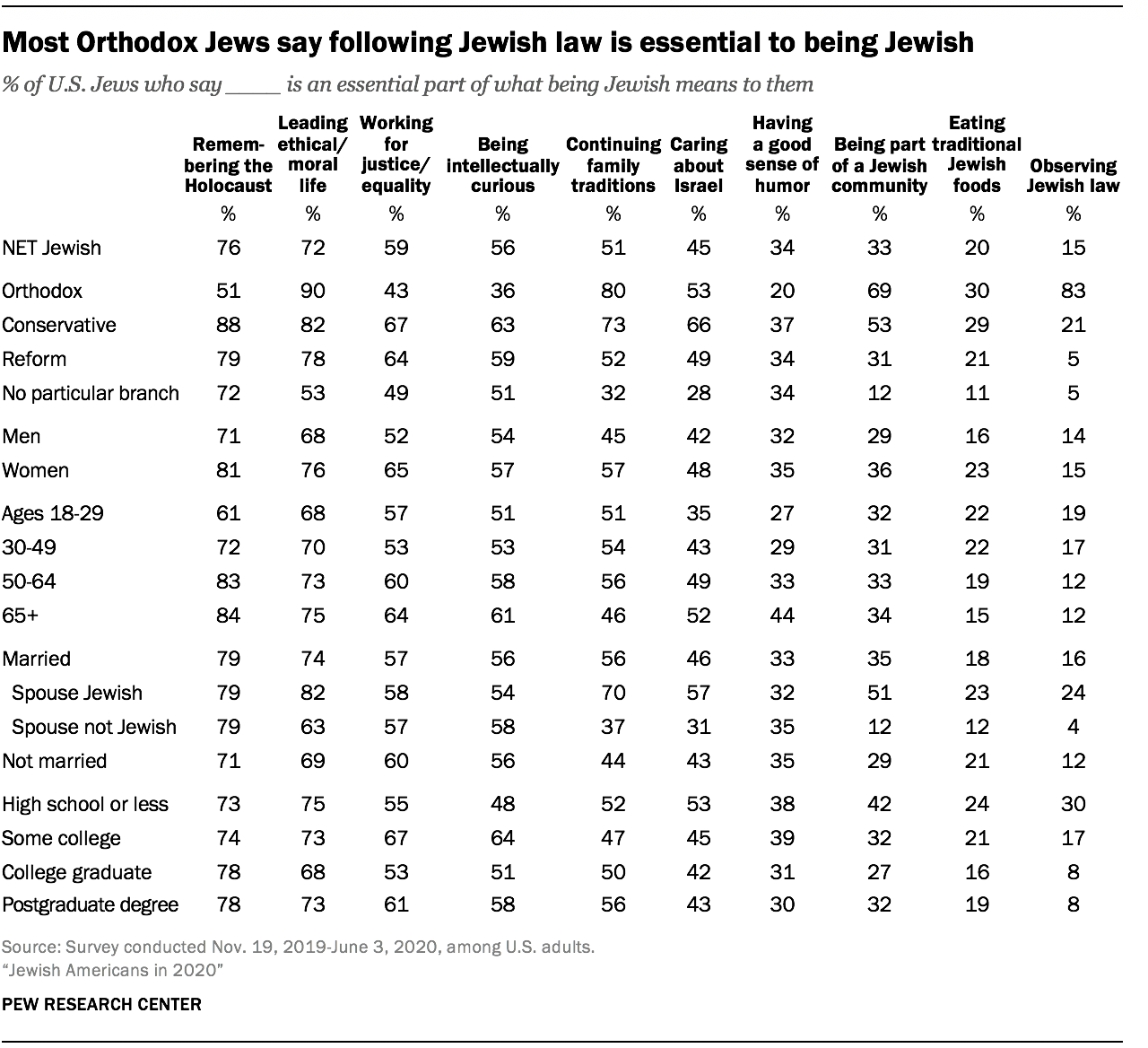

Many American Jews prioritize cultural components of Judaism over religious ones. Most Jewish adults say that remembering the Holocaust, leading a moral and upstanding life, working for justice and equality in order, and beingness intellectually curious are "essential" to what it means to them to exist Jewish. Far fewer say that observing Jewish police force is an essential part of their Jewish identity. Indeed, more consider "having a good sense of humour" to be essential to beingness Jewish than consider following halakha (traditional Jewish law) essential (34% vs. xv%).

Orthodox Jews are a striking exception to many of these overall findings. They are among the virtually highly religious groups in U.S. society – along with White evangelicals and Black Protestants – in terms of the share who say religion is very important in their lives. A plurality of Orthodox Jews say that being Jewish is mainly nigh religion alone (forty%), and they are the only subgroup in the survey who overwhelmingly feel that observing halakha is essential to their Jewishness (83%). Fully three-quarters of the Orthodox say they find a swell deal of meaning and fulfillment in their religion, exceeded simply by the share who feel that fashion about spending time with their families (86%). And 93% of Orthodox Jews say they believe in God as described in the Bible, compared with a quarter of Jews overall.

Identification with branches of American Judaism

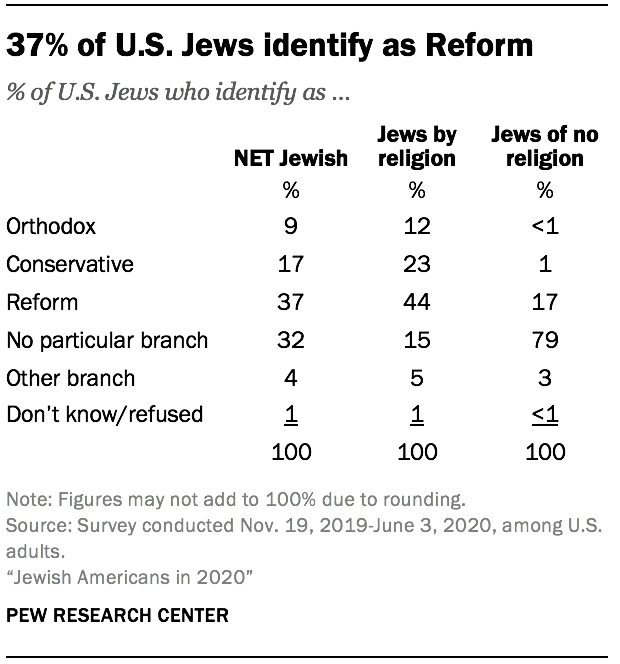

More than one-half of U.S. Jews identify with the Reform (37%) or Conservative (17%) movements, while about one-in-ten (9%) identify with Orthodox Judaism. One-third of Jews (32%) do not identify with whatsoever particular Jewish denomination, and 4% identify with smaller branches – such as Reconstructionist or Humanist Judaism – or say they are connected with multiple streams of U.Due south. Judaism. Among Jews by religion, branch affiliation generally mirrors the broader blueprint amongst Jews overall. Most Jews by religion place with either Reform (44%) or Conservative (23%) Judaism, and fewer say they do not belong to a detail denomination (15%). Most Jews of no religion, on the other hand, exercise not place with any institutional co-operative or stream of Judaism (79%), while the remainder largely describe themselves as Reform Jews (17%).

More than one-half of U.S. Jews identify with the Reform (37%) or Conservative (17%) movements, while about one-in-ten (9%) identify with Orthodox Judaism. One-third of Jews (32%) do not identify with whatsoever particular Jewish denomination, and 4% identify with smaller branches – such as Reconstructionist or Humanist Judaism – or say they are connected with multiple streams of U.Due south. Judaism. Among Jews by religion, branch affiliation generally mirrors the broader blueprint amongst Jews overall. Most Jews by religion place with either Reform (44%) or Conservative (23%) Judaism, and fewer say they do not belong to a detail denomination (15%). Most Jews of no religion, on the other hand, exercise not place with any institutional co-operative or stream of Judaism (79%), while the remainder largely describe themselves as Reform Jews (17%).

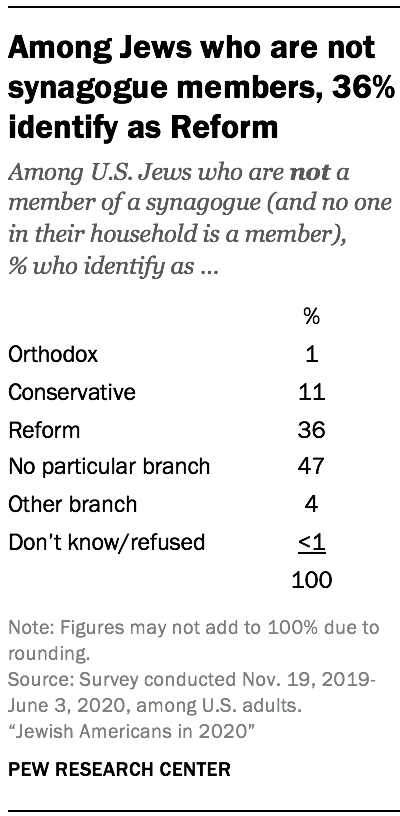

It is often assumed that for U.South. Jews, co-operative affiliation goes hand in mitt with synagogue membership – e.g., they belong to a Conservative synagogue, and so they identify as Conservative, or they belong to a Reform temple, and then they identify every bit Reform. But this is non e'er the case, because the percentage of Jewish adults who identify with some branch of U.S. Judaism (67%) is considerably college than the percentage who are synagogue members or accept someone in their household who is a synagogue fellow member (35%).

It is often assumed that for U.South. Jews, co-operative affiliation goes hand in mitt with synagogue membership – e.g., they belong to a Conservative synagogue, and so they identify as Conservative, or they belong to a Reform temple, and then they identify every bit Reform. But this is non e'er the case, because the percentage of Jewish adults who identify with some branch of U.S. Judaism (67%) is considerably college than the percentage who are synagogue members or accept someone in their household who is a synagogue fellow member (35%).

Among Jews who are neither synagogue members themselves nor alive in a household where anyone else belongs to a synagogue, 47% do non identify with any institutional branch or stream of Judaism. But roughly half identify as Reform (36%), Conservative (11%), Orthodox (ane%) or another Jewish denomination (4%), even though they signal that, at nowadays, they have no formal connexion to a synagogue. This design is similar when looking only at respondents who are themselves non members of a synagogue, regardless of the status of others in their household. There could be multiple reasons for this, including Jewish denominational attachments retained since childhood, participation in Chabad or other synagogues that do not have a formal membership structure, and financial barriers to synagogue membership, amidst other possibilities. (The survey asked divide questions about branch affiliation, synagogue membership and synagogue attendance, without probing the exact connections; it did non inquire people who identify equally Reform Jews, for case, whether the synagogue they attend, or belong to, is a Reform synagogue.)

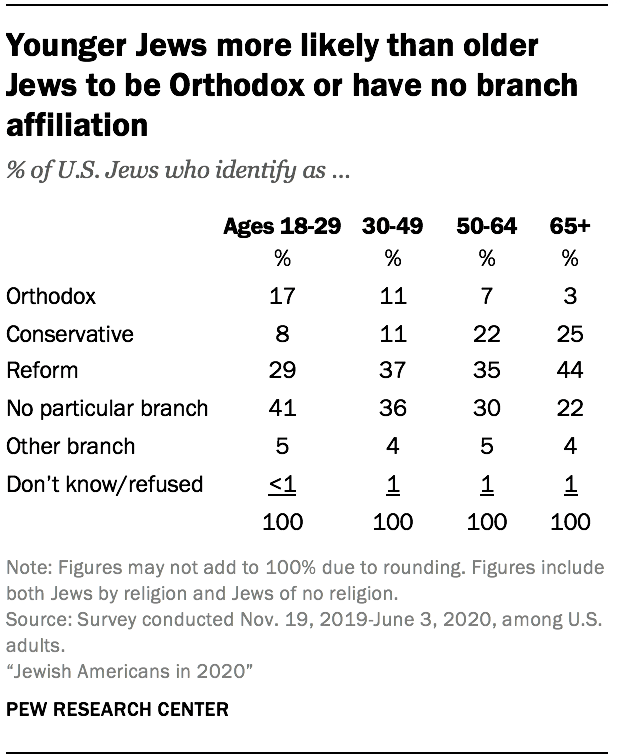

Jewish adults ages eighteen to 29 are particularly likely to identify every bit Orthodox (17%), compared with those who are 30 and older, of whom vii% are Orthodox. The youngest Jewish adults as well are more inclined than their elders to have no branch affiliation (41%), while smaller shares are Reform (29%) or Conservative (8%).

Jewish adults ages eighteen to 29 are particularly likely to identify every bit Orthodox (17%), compared with those who are 30 and older, of whom vii% are Orthodox. The youngest Jewish adults as well are more inclined than their elders to have no branch affiliation (41%), while smaller shares are Reform (29%) or Conservative (8%).

At the other end of the historic period spectrum, 44% of Jews ages 65 and older identify with the Reform movement, and a quarter say they are Conservative.

Jews less inclined than U.S. adults as a whole to consider religion very important

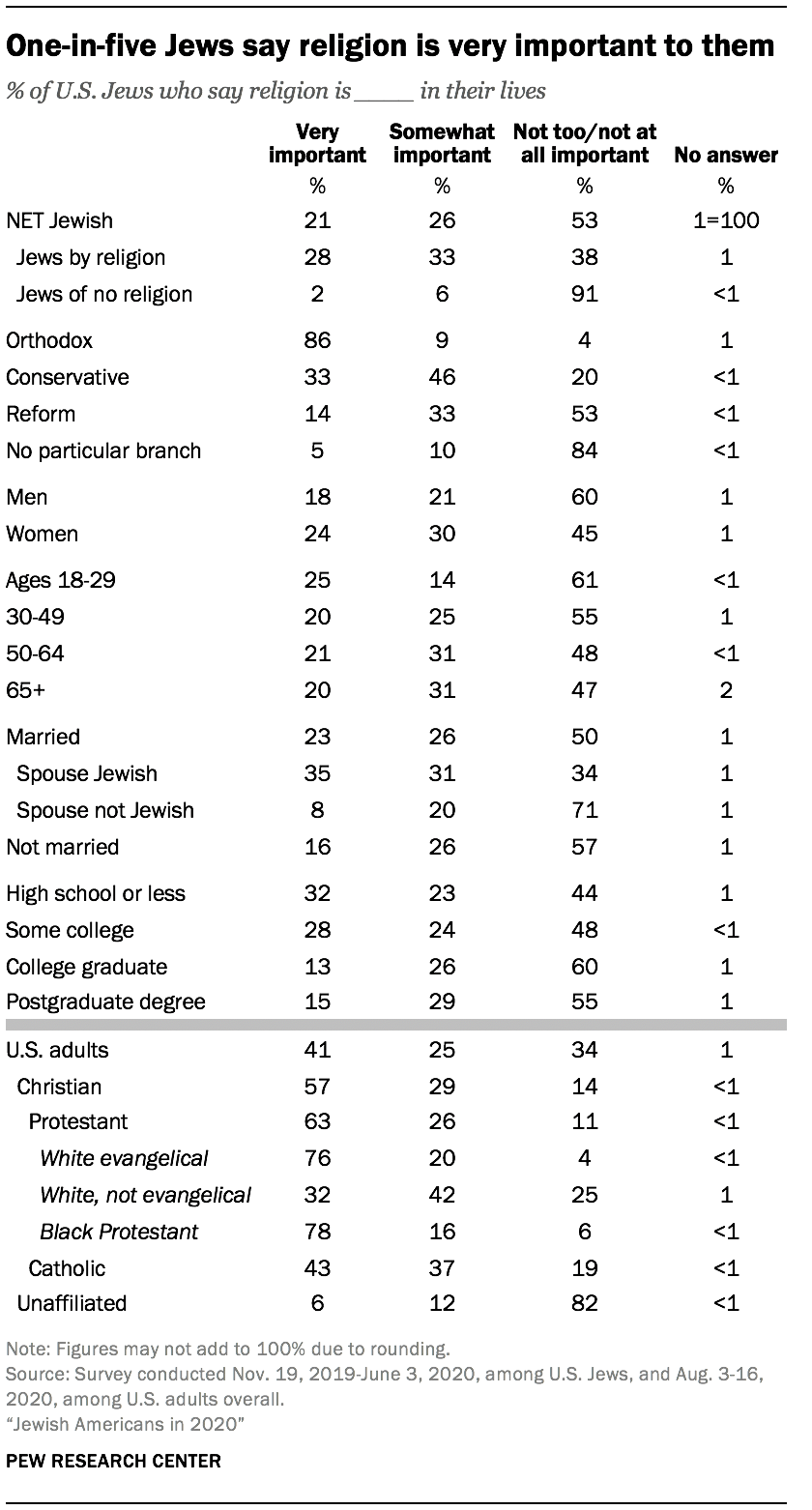

Virtually half of U.S. Jews say organized religion is either "very" (21%) or "somewhat" (26%) important in their lives, while 53% say faith is "not also" or "not at all" important to them personally.

Virtually half of U.S. Jews say organized religion is either "very" (21%) or "somewhat" (26%) important in their lives, while 53% say faith is "not also" or "not at all" important to them personally.

Jews by organized religion are far more than likely than Jews of no religion to say religion is at least somewhat of import in their lives (61% vs. 8%). And Orthodox Jews are especially probable to say that religion is important: Nearly ix-in-ten (86%) say religion is very of import to them, compared with a tertiary of Conservative Jews (33%) and 14% of Reform Jews who consider religion very important in their lives.

Religion is more important to Jewish women, on average, than to Jewish men. Jewish adults ages 30 and older are more likely than those under 30 to say organized religion is at least somewhat of import to them (49% vs. 39%). And two-thirds of married Jews who accept a Jewish spouse say organized religion is very (35%) or somewhat (31%) of import to them, while far fewer intermarried Jews say this (8% very important, 20% somewhat important).

Jews who did not obtain college degrees are more than inclined to say that religion is very of import in their lives. For instance, about a third of U.S. Jews whose formal pedagogy stopped with high schoolhouse (32%) say organized religion is very important, compared with xiii% of those with available'due south degrees and 15% of those with postgraduate degrees.

Compared either with U.S. Christians or with the adult public overall, U.Southward. Jews are far less likely to say that faith is important in their lives. Still, Orthodox Jews rank among the about religiously devout subgroups in the country by this measure; 86% say organized religion is very important in their lives, as do 78% of Blackness Protestants and 76% of White evangelical Protestants, two of the about highly religious Christian subgroups. Meanwhile, Jews of no religion are even more than likely than religiously unaffiliated Americans to say religion is "non as well" important or "not at all" important to them (91% vs. 82%).

The fact that many Jews say religion is relatively unimportant in their lives does not necessarily hateful their Jewish identity is not meaningful to them. In fact, three-quarters of U.South. Jews say that "being Jewish" is either very of import (42%) or somewhat important (34%) in their lives, while only 23% say it is not too or not at all important to them.

The fact that many Jews say religion is relatively unimportant in their lives does not necessarily hateful their Jewish identity is not meaningful to them. In fact, three-quarters of U.South. Jews say that "being Jewish" is either very of import (42%) or somewhat important (34%) in their lives, while only 23% say it is not too or not at all important to them.

Jews by religion are far more likely than Jews of no faith to say that being Jewish is very important to them (55% vs. 7%); 55% of Jews of no religion say beingness Jewish is of trivial importance to them.

Nearly all Orthodox Jews in the survey (95%) describe beingness Jewish every bit very of import in their lives. A majority of Bourgeois Jews likewise say being Jewish is very important (69%). Fewer Reform Jews (40%) and Jews of no denomination (17%) say the aforementioned.

Married Jews are more likely than those who are non married to say that beingness Jewish is central to their lives (48% vs. 33%). Being Jewish tends to be particularly of import for Jews who have a Jewish spouse (64% say it is very important).

To U.S. Jews, beingness Jewish is not simply about organized religion

There is no 1 fashion that American Jews think about being Jewish, every bit the survey makes clear. When asked whether being Jewish is mainly a thing of faith, beginnings or civilization, some Jewish respondents pick each of those things, and many cull some combination of them. In fact, among the nearly common answers – expressed past about one-in-v U.South. Jews (nineteen%) – is that beingness Jewish is nigh religion, ancestry and civilization.

Similar shares say being Jewish is mainly a matter of just civilization (22%) or just ancestry (21%). About half every bit many (eleven%) say being Jewish is mainly about religion alone. The residual requite other responses, such as that being Jewish is near both ancestry and civilization (x%).

All told, about half mention ancestry amid their responses (52%). A similar share point to culture either alone or in combination with other answers (55%). But fewer mention faith (36%), suggesting that most U.Due south. Jews do non encounter being Jewish as primarily near religion.

Even among Jews by organized religion, just 44% mention faith every bit a principal facet of Jewish identity, although Orthodox Jews stand out in this regard: twoscore% say being Jewish is nigh only organized religion, and an additional 3-in-ten Orthodox adults say it is near some combination of religion, ancestry, and civilisation, or all three of these.

The vast bulk of Jews of no religion say that for them, being Jewish is mainly a matter of beginnings (41%), culture (25%) or both (15%).

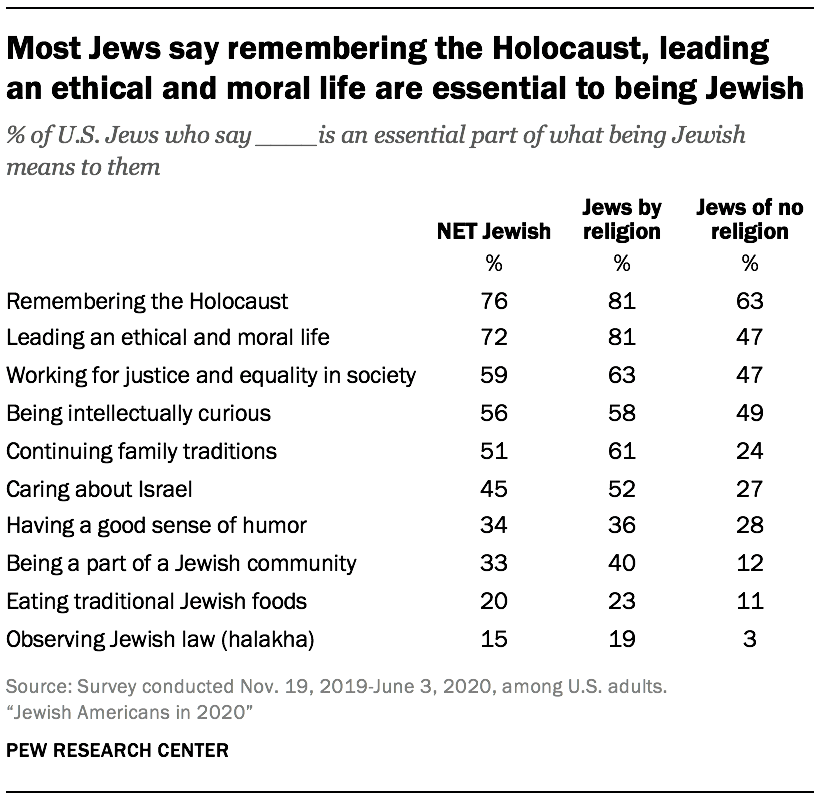

The survey asked Jews whether each of ten attributes and activities is essential, important but not essential, or not of import to what being Jewish means to them. The answers show that to U.Southward. Jews, being Jewish is about many things. Fully iii-quarters (76%) say remembering the Holocaust is an essential office of what being Jewish means to them, and well-nigh as many (72%) say leading an ethical and moral life is essential. Majorities of U.S. Jews say working for justice and equality in social club (59%) and being intellectually curious (56%) are essential to existence Jewish.

The survey asked Jews whether each of ten attributes and activities is essential, important but not essential, or not of import to what being Jewish means to them. The answers show that to U.Southward. Jews, being Jewish is about many things. Fully iii-quarters (76%) say remembering the Holocaust is an essential office of what being Jewish means to them, and well-nigh as many (72%) say leading an ethical and moral life is essential. Majorities of U.S. Jews say working for justice and equality in social club (59%) and being intellectually curious (56%) are essential to existence Jewish.

Half of U.S. Jews say continuing family unit traditions is an essential part of their Jewish identity (51%), and 45% say caring nearly Israel is essential. One-tertiary or fewer mention having a sense of humor (34%), existence part of a Jewish community (33%), eating traditional Jewish foods (20%) or observing Jewish law (15%) equally essential aspects of their Jewish identity.

The survey also asked respondents to describe in their ain words annihilation else that is essential to what being Jewish means to them; see topline for results.

Nine of these items (forth with the final, open-concluded question) were included in the 2013 survey, while the item about continuing family unit traditions is new. In terms of relative importance, respondents ranked the items similarly in each of the two surveys. For instance, remembering the Holocaust, leading an ethical and moral life, and working for justice and equality were the top iii responses in both 2013 and 2020.21

While Jews by religion are more likely than Jews of no religion to consider each of the 10 attributes or activities in the 2020 survey essential to being Jewish, both groups more often than not rank the items in a similar order. Majorities of both Jews by faith and Jews of no organized religion cite remembering the Holocaust equally essential, and both groups rank observing Jewish law and eating traditional foods toward the bottom of the list.

Despite these similarities, there are large gaps between the two groups on a few aspects of Jewish identity. For instance, Jews past religion are far more likely than Jews of no religion to say that continuing family unit traditions is essential to what it means to them to be Jewish (61% vs. 24%). And Jews by religion are well-nigh twice as probable every bit Jews of no faith to say that caring about Israel is essential (52% vs. 27%).

Those with a Jewish spouse differ significantly from those without one on the importance of standing family traditions. Among Jews with a Jewish spouse, seven-in-ten say continuing family traditions is essential to what it ways to them to exist Jewish, while far fewer Jews married to spouses who are not Jewish (37%) say the same.

Older Jews are more likely than younger generations to run across sure things as essential to being Jewish. Compared with Jewish adults under the age of 30, larger shares of those 65 and older rank remembering the Holocaust, caring about Israel, beingness intellectually curious and having a good sense of sense of humour as essential parts of their Jewish identity. Withal, younger Jews more probable than the eldest cohort to say that observing Jewish law is essential to being Jewish (nineteen% vs. 12%).

What's essential to being Jewish as well tends to vary according to the respondent'south branch or stream of Judaism. Orthodox Jews are more probable than the not-Orthodox to say that following Jewish police and being part of a Jewish customs are essential to what it means to them to exist Jewish. Non-Orthodox Jews are more than likely than the Orthodox to say that remembering the Holocaust, being intellectually curious and having a good sense of humour are essential.

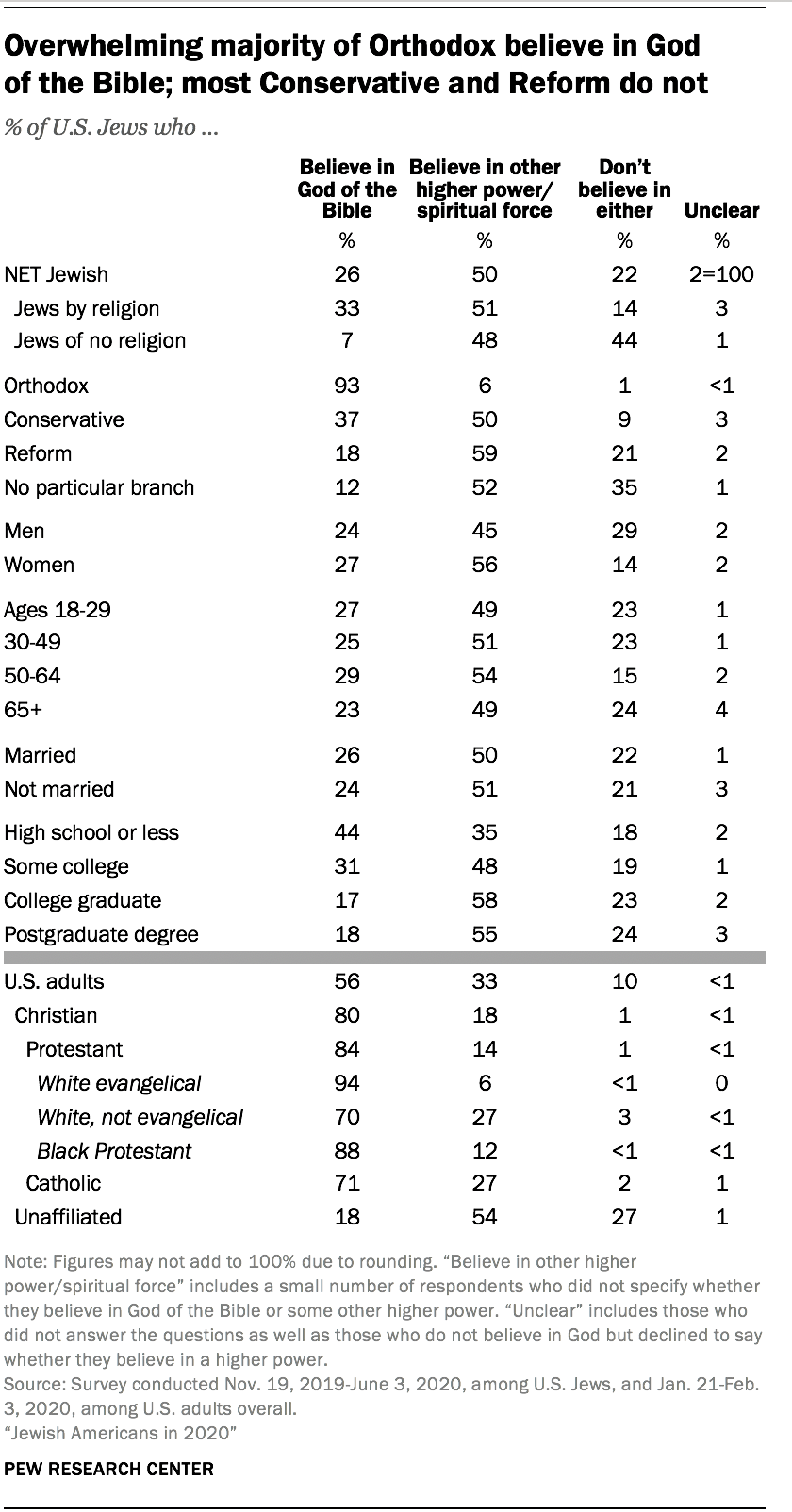

3-quarters of Jews believe in college ability of some kind, simply just one-quarter believe in God equally described in the Bible

Three-quarters of U.South. Jews say they believe in God or some spiritual strength in the universe, including 26% who say they believe in "God as described in the Bible" and about twice every bit many (50%) who believe in some other spiritual force. Belief in God is much more widespread among Jews past religion than amid Jews of no faith. But even among Jews by religion, 14% say they practice not believe in whatever higher power or spiritual forcefulness. Meanwhile, 44% of Jews of no religion say they do not believe in any higher ability.

Three-quarters of U.South. Jews say they believe in God or some spiritual strength in the universe, including 26% who say they believe in "God as described in the Bible" and about twice every bit many (50%) who believe in some other spiritual force. Belief in God is much more widespread among Jews past religion than amid Jews of no faith. But even among Jews by religion, 14% say they practice not believe in whatever higher power or spiritual forcefulness. Meanwhile, 44% of Jews of no religion say they do not believe in any higher ability.

Nine-in-10 Orthodox Jews (93%) say they believe in the God of the Bible, compared with 37% of Conservative Jews, 18% of Reform Jews and 12% of Jews with no denomination.

U.S. Christians are far more probable than U.S. Jews to say they believe in God as described in the Bible, and far less likely to say they believe in another college ability – or no higher power at all.

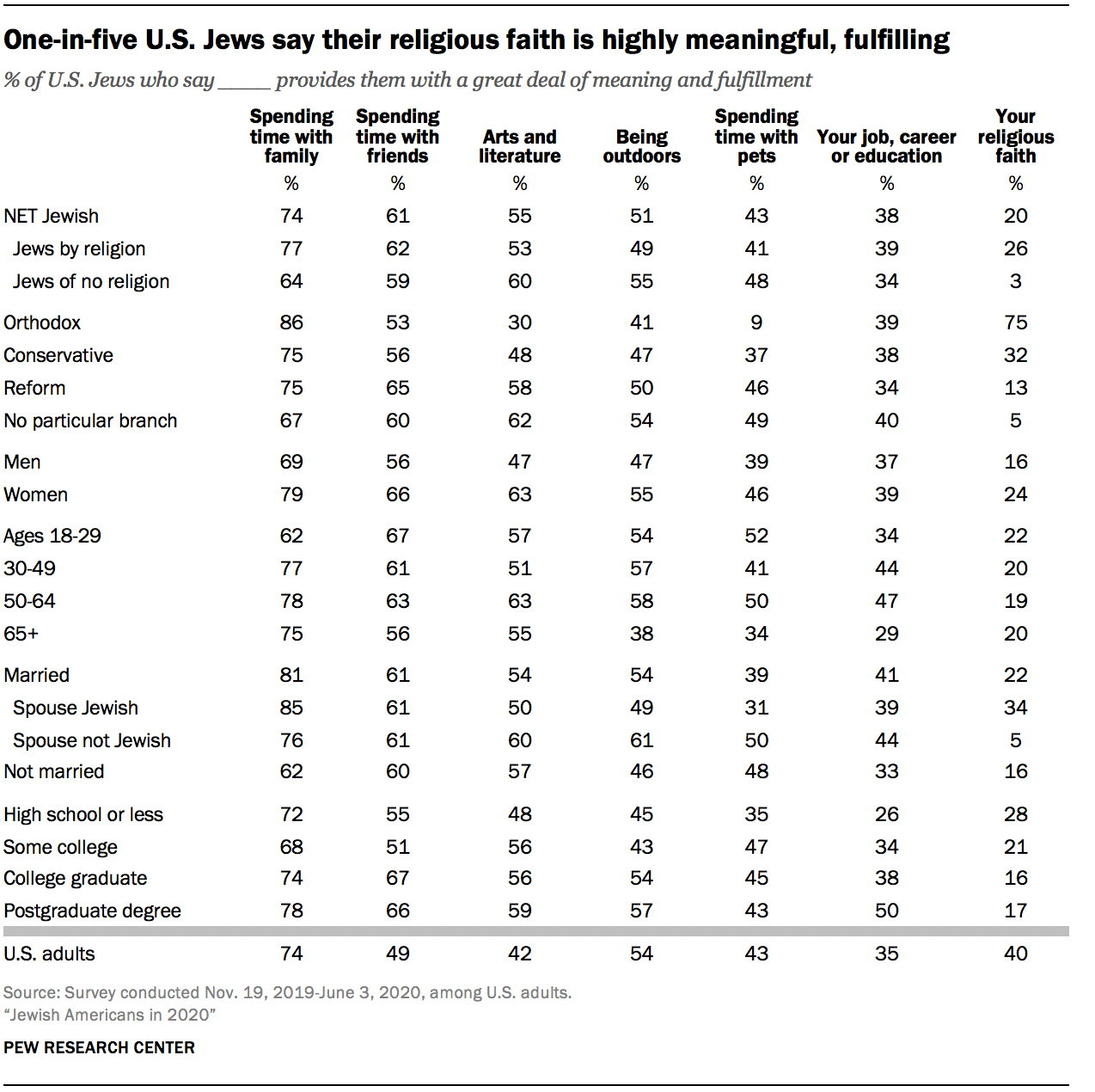

American Jews derive a great deal of meaning from spending time with family and friends

The survey also included a set of questions request respondents to rate how much significant and fulfillment they depict from each of seven possible sources: spending time with family unit; spending time with friends; their religious faith; being outdoors and experiencing nature; spending time with pets or animals; their job, career or education; and arts and literature, such as music, painting and reading.

3-quarters of U.S. Jews say they derive a smashing deal of meaning from spending time with their family (74%), and six-in-ten observe a bully bargain of fulfillment in spending time with friends (61%). Arts and literature (55%), spending time outdoors (51%), spending time with pets (43%) and jobs (38%) also are common sources of pregnant and fulfillment. Among Jews, religious faith is by far the least mutual source of meaning of all the options presented by the survey; just one-in-five U.Southward. Jews say they become a great deal of meaning and fulfillment from their faith.

Jews by faith are somewhat more likely than Jews of no religion to say they draw a peachy deal of meaning from their families and from their religion, although fifty-fifty among Jews past religion, only a quarter say their religious faith carries a nifty bargain of significant.

In that location are also differences in where Jews find meaning based on their denominational affiliation. Nigh ix-in-x Orthodox Jews say they find spending time with family very meaningful (86%), compared with 3-quarters of Bourgeois and Reform Jews. And three-quarters of the Orthodox notice a great deal of meaning in their religious faith, versus 32% of Bourgeois and only 13% of Reform Jews. Conversely, non-Orthodox Jews are far more than probable than the Orthodox to find pregnant in arts and literature likewise as pets or animals.

Jewish Americans are less likely than U.S. adults equally a whole to observe a great bargain of meaning in their religious organized religion (20% vs. 40%).

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/2021/05/11/jewish-identity-and-belief/

0 Response to "How To Tell If Someone Is A Jew"

Post a Comment